After my initial outing to Delaware in search of history and scenery, I was pumped to return and complete my route. And I was hoping to jump on foot from Maryland, across Pennsylvania, and into Delaware. I’ve been to known to exaggerate on occasion, but this is not one of those times. Read on!

A Crumbling Mansion, Complete with Ghost?

Three weeks after my first trip, I arrived bright and early at Elk Landing, Maryland, a few miles shy of Delaware.

Elk Landing was the site of Fort Hollingsworth. During the War of 1812, Fort Hollingsworth and the nearby Fort Defiance successfully repulsed a British Naval attack on the city of Elkton. Fort Hollingsworth was dismantled in 1815, but archaeologists have determined that it was located to the right of the Hollingsworth Mansion, along the Little Elk River. The first floor of this mansion was constructed in about 1800. A fire in 1848 left only the walls standing, but the home was repaired and the second story and wing on the right were added. It remained in the Hollingsworth Family until 1999, when the town of Elkton acquired the property.

This old stone building is believed to have been a home and trading post, built in about 1780. A log cabin previously stood adjacent to the stone house and was probably the trading post started by John Hans Steelman in the late 1600s, to exchange goods with the local Native Americans. The Historic Elk Landing Foundation has restored the stone house from its earlier state of disrepair. (Old photos of Elk Landing courtesy of the Foundation.)

This section of the Little Elk River used to be the site of a major shipbuilding operation. About 70 “schooner barges” were built here, typically over 200 feet in length, before the Army Corps of Engineers stopped dredging the river in 1911. Now, the river can only be navigated by canoes, kayaks, and other small craft.

Sharp-eyed Mercedes aficionados will recognize that the SL550 is now wearing its proper summer performance wheels and tires.

Near downtown Elkton and immediately next to a shopping center, Holly Hall stands alone, desperately in need of restoration. General James A. Sewell, who commanded the Second Battalion at Fort Defiance, built this magnificent home in the 1810s. Sadly, Holly Hall has been vacant and deteriorating since at least the early 1930s. The good news is that Preservation Maryland agreed in 2016 to help save the endangered building. The bad news is that little has happened since then.

Holly Hall has been the subject of many a ghost story over the years (see Eastern Entities for several of the more popular ones). The best-documented of these[/url] is that Gen. Sewell and his son had a colossal falling-out. Years later, when his son returned from war, badly wounded, the General refused him entry into Holly Hall. The son died the next day, and many people subsequently reported seeing a young man in military uniform roaming the hallways and grounds of the house. It’s a pretty good ghost story, but it’s hampered by a couple of relevant facts: First, Gen. Sewell had only one son (James M. Sewell), and that son outlived his father by 39 years. And second, there were no U.S. wars between 1823 when James M. was born and 1842 when Gen. Sewell passed away. Oh well… As Mark Twain famously said, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story”!

Since no one was looking, another “SL in front of a mansion” photo occurred. That pesky car just can’t help itself.

In a Hurry To Get Married?

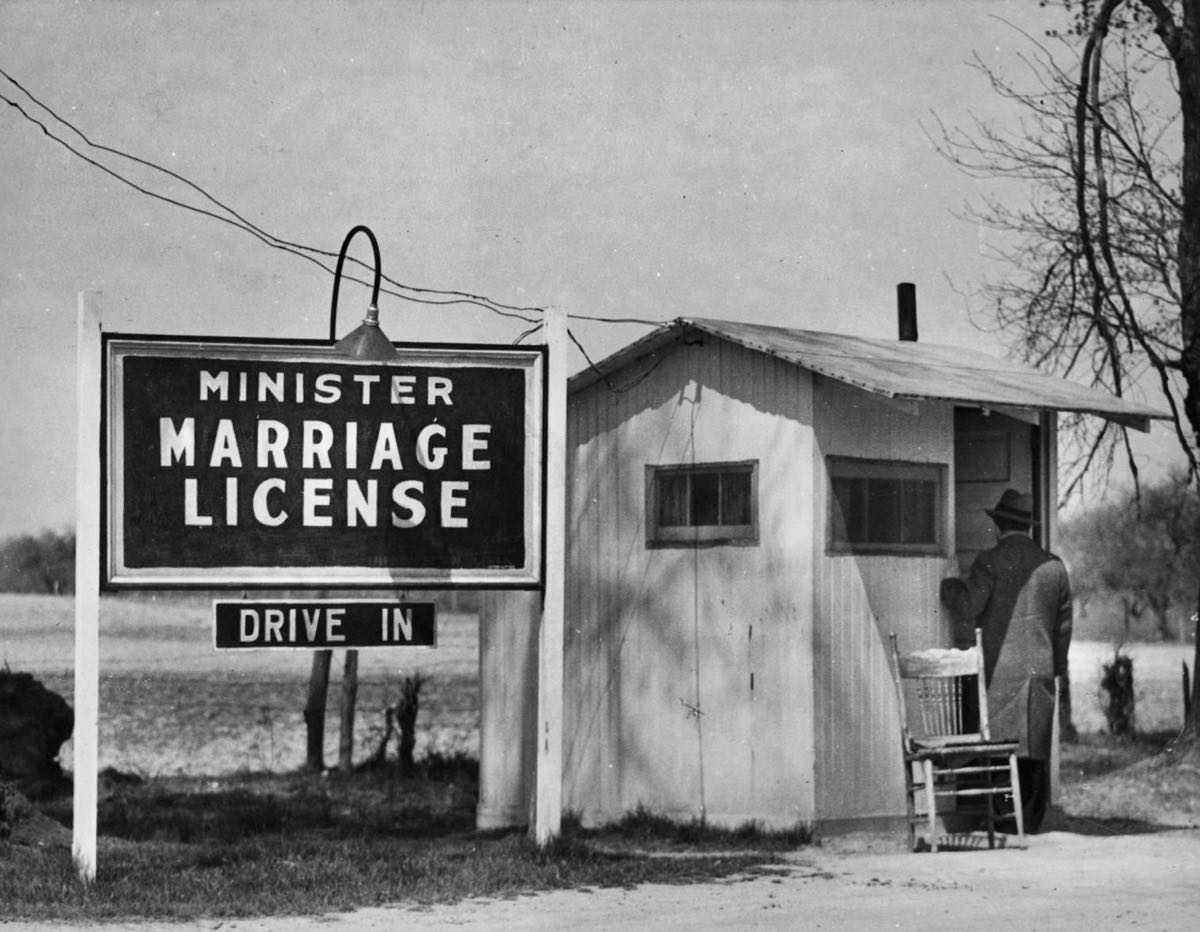

In the early 1900s, northern states began enacting laws that required waiting periods, blood tests, and other restrictions before a couple could get married. Before long, impatient couples from New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and other states began flooding into Maryland, where there was no waiting period. Elkton, being the closest county seat to the northeast states, became the “Marriage Capital of the East Coast.” At its peak in 1938, 16,054 marriages were performed in Elkton—a town of only 3,000 residents. Actors Debbie Reynolds, Joan Fontaine, Cornell Wild, and Martha Raye were all married here. There were 20 marriage chapels on Main Street alone, and you could obtain a marriage license on a drive-through basis.

This photo pretty much sums up a typical arrival in Elkton: Irene Mariotti and Lucian Slepski were wed on June 12, 1941. The onset of World War II substantially increased the number of quickie weddings. (Photo courtesy of the Baltimore Sun.)

The Little Wedding Chapel was the last of the marriage mills in Elkton. Singer Billie Holliday, baseball star Willie Mays, and Nixon Attorney General John Mitchell were all married here. (No, Horace, not to each other!) After Maryland enacted a 48-hour waiting period, the chapel continued on for many years, but even it closed in 2017. Today it’s just another vacant building.

Some of the Elkton businesses still looked to be doing well, but many owners have moved out, citing problems with homelessness and heavy-handed city regulations.

The handsome Elkton Armory has provided training to the Maryland National Guard and dances and other social functions to the town since 1915. In 2018, however, it was declared to be “surplus property” by the Maryland Military Department. Last year, the Town of Elkton purchased the armory and plans to continue its use as a social center.

Homelessness is not solely a twenty-first century problem. In 1768, the Maryland State Legislature required every county to create an almshouse for the care of poor individuals and families. The Cecil County Almshouse was constructed in 1788 and continued in operation until 1952. If able, residents would work in the fields to provide food for the facility and for sale to the public. The Potters Field across the road was the final resting place for those who died here. Since the 1950s, the former almshouse has been home to the Oblate Sisters of St. Francis de Sales.

Jumping across Pennsylvania

After reading William Ecenbarger’s excellent book Walkin’ the Line, I became determined to learn more about the famous surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon. They were hired by the Maryland Calverts and Pennsylvania Penns to settle the long-disputed boundary between the two colonies. The Mason-Dixon Line is well known as the divider between the northern free states and the southern slave states. Less well known is the fact that the surveyors also needed to precisely determine the boundary between Maryland and Delaware. These boundaries had been specified by British Kings Charles I (Maryland) and Charles II (Pennsylvania and Delaware) in 1632 and 1681, respectively. These royals lived 3,500 miles away and had never been to North America. Moreover, the existing territorial surveys were not particularly accurate.

The southern boundary between Maryland and Delaware starts at Fenwick Island on the Atlantic Ocean and runs due west to a “Middle Point.” Mason and Dixon accepted the accuracy of the Middle Point, and began their survey there. From this point, a “Tangent Line” runs northerly until it reaches an exact tangent with the “New Castle Circle” centered on New Castle, DE. From the Tangent Point, a “North Line” goes straight north to its intersection with the “West Line.” Got all that? The Kings Charles thought the North Line would intersect the West Line exactly where it met the New Castle Circle—but they were wrong. It took Mason and Dixon 2 years to get the Tangent Line right, but they did, and subsequent modern surveys have found it accurate to within a meter. (Map courtesy of East of the Mason-Dixon Line by Roger E. Nathan.)

As shown in this detail map from Walkin’ the Line, Mason and Dixon placed a stone marker at the Tangent Point, where the 82-mile-long Tangent Line exactly met the New Castle Circle at a right angle. About a third of a mile north of the Tangent Point, they placed another stone at the exact location where the North Line, Tangent Line, and New Castle Circle all intersect. I wanted to find both of these stones, if they even still existed. (For information about the “Stargazers’ Stone” shown on the map, check out my story Indian Hannah and the Stargazers’ Stone.)

It took a lot of online searching and a good GPS, but I found the Tangent Point stone. It sits on the outskirts of a modern housing development, immediately adjacent to a larger marker from an 1849 survey. Both are protected by a sturdy iron cage. I’m not sure how a thief would make off with a Mason-Dixon marker, since each one weighs as much as 700 pounds, but they do go missing from time to time.

Finding the Intersection Point stone was far harder. I had to look at a host of old maps, do some geometric calculations, and add a little “Kentucky windage” before I could ascertain its approximate position. And then I discovered that modern Highway 279 sits right over where the stone might once have been…

I was about to give up on the Intersection Point when I found a reference at the National Geodetic Survey website. When the highway was being built, apparently the highway department felt bad about removing the historic marker—so they buried it a couple of feet and put a manhole cover over it. See the manhole cover in the above photo? Yep, the original stone is right underneath. In the background are a convenient liquor store and Madam Selena’s Spiritual Psychic Readings. (Note where I parked.) (Photo of the Intersection Point stone courtesy of the National Geodetic Survey.)

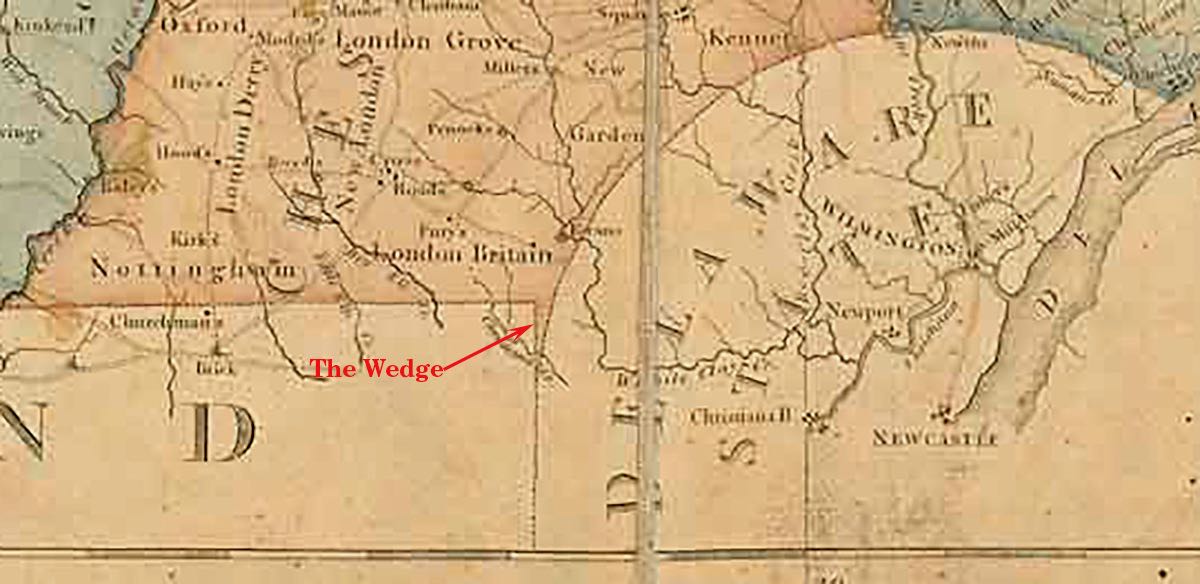

As shown in the detail from this 1792 map of Pennsylvania, Mason and Dixon’s precise measurements revealed a gap between Maryland and Delaware. It was clear that Maryland was west of the Northern Line and Delaware was east of the New Castle Circle. The only thing that could therefore be in the middle was Pennsylvania. This 684-acre area became known as “The Wedge,” claimed by both Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Before embarking on my trip, it occurred to me that the very tip of The Wedge—the Intersection Point— was infinitesimally small, and that, just north of that point, this little bit of Pennsylvania would be narrow enough to jump across. I could literally jump from the state of Maryland, across Pennsylvania, and land in the state of Delaware. An automatic road trip goal, naturally!

There were two complications, however. First, Highway 279 is a very busy roadway, and a jumpable part of the Wedge was in the middle of the westbound lanes. And second, at 72 I’m not really all that spry anymore. Regardless, I set up the camera on a tripod by the side of the highway, gauged the timing of traffic between two stoplights, and ventured forth…

Success—I jumped clean across Pennsylvania! Well, sort of. I neglected to mention a third complication. Over the years, The Wedge had become a major nuisance to residents, visitors, and state governments alike. With jurisdiction of the area unclear, criminals flocked to The Wedge, committed their crimes, and could immediately cross a state line away from whichever state’s police might be chasing them. Residents believed they lived in Delaware, perhaps because they paid Delaware taxes, and they firmly resisted Pennsylvania’s efforts to tax them. In 1892, Pennsylvania yielded to Delaware’s demand for The Wedge, but the change was not official until an act of Congress in 1921. So, technically, I had jumped over what used to be Pennsylvania. I was 100 years late (but I’ll still take credit!)

The Ticking Tomb

Having accomplished my primary goal for the trip, it was time to move on. In the process, I drove through the “Old College” section of the University of Delaware, in Newark. Other than the number of trees and balance between the number of male and female students, it didn’t look so much different from the 1875 photo (courtesy of the University of Delaware).

On the way to the London Tract Baptist Church, I found the 1849 Arc Corner Stone marking where the New Castle Circle intersects with the eastward extension of the Mason-Dixon West Line. Prior to 1921, it was the northeast corner of The Wedge.

In the late 1600s, a group of 16 Welsh Baptists immigrated to America, settled in Philadelphia, and formed a new church there. Baptists being Baptists—sorry Cathy and Kim!—a group of them split off and started the Welsh Tract Old School Baptist Church in Newark. Sometime later, a further portion of the Welsh Tract group split off and formed the London Tract Old School Baptist Church a few miles north of the Arc Corner Stone in Pennsylvania. Prior to 1663, this land was home to the Minguannan tribe of Lenape Native Americans, who had lived here for 8,000 years.

Of the graves surrounding the church, this one stood out. Did it collapse of its own accord, or were their grave robbers at work?

A longstanding legend says that a ticking sound can be heard emanating from one of the oldest graves in the cemetery. The highly regarded Civil War journalist, George Alfred Townsend (“Gath”) devoted an entire chapter to this story in his book Tales of the Chesapeake, stating that he himself heard the sound quite clearly when he pressed his ear to the gravestone. Townsend tells a marvelous tale of a toddler having swallowed Charles Mason’s miniature chronometer while the surveyors were working in this area in 1764, and how the watch continued to run through the individual’s life and even thereafter. In Walkin’ the Line, William Ecenbarger cites State Park Ranger Gay Overdevest as having heard the ticking sound herself on a number of occasions. It’s a great story, but there is no indication in the churchyard as to which grave is the “ticking tomb.” I’ll find it the next time!

Since the small parking area at London Tract was full, I had to park the SL550 in someone’s front yard. Fortunately, it didn’t look like they were home.

Mansions, Anyone?

From the church, I crossed the New Castle Circle back into Delaware and almost immediately found the North Star House. It was built in 1723 and is said to have been part of the Underground Railroad, providing a safe haven for enslaved African Americans escaping to freedom in Pennsylvania. In the late 1800s it was owned by T. Coleman du Pont, the former president of his family’s business and a U.S. Senator from Delaware. Another Senator who lived here in the early 1970s was a fellow named Joe Biden.

Speaking of former du Pont mansions previously owned by Joe Biden, why here’s another one! It was built in 1930, but by 1975 it was vacant, run down, and in danger of demolition. The current President bought it as a fixer-upper and, well, spent the next 20 years fixing it up. He sold the house in 1996. Despite my best efforts, I was unable to learn which member of the du Pont family lived here or any other history about the house.

After finding two former du Pont mansions, I was anxious to make it a “hat trick”—i.e., three in a row. I had heard rumors of a long-abandoned “Gibraltar” mansion in the outskirts of Wilmington, but did it still exist? John Brincklé built the mansion in 1844 on an estate of more than 300 acres. By the time Hugh and Isabella Mathieu du Pont Sharp bought the place in 1909, the property occupied “merely” one full city block. The Sharps hired Marian Cruger Coffin (1876-1957) to design and create elaborate gardens. Ms. Coffin had graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1904, one of only four women in her class. Unable to find a job in this male-dominated field, she started her own company and soon became a highly regarded landscape architect. In addition to Gibraltar, her 130 career garden designs included those for the University of Delaware and the du Pont Winterthur estate. (Photo of Marian Coffin courtesy of the Winterthur Museum; photo of Ann, Hugh, and Bayard Sharp in the Gibraltar swimming pool courtesy of Delaware Today.)

Locating the Gibraltar estate, I was pleased to learn that the garden, after a long period of total neglect, is now under the care of Preservation Delaware and is open to the public. The swimming pool has been repurposed into a reflecting pool.

The aptly named Marian Coffin Garden has many statues, which were acquired by the Sharps from around Europe.

A beautiful, curving, marble staircase led from one garden terrace to the next—and revealed the Gibraltar mansion still sitting on top of the hill.

Unfortunately, the mansion has been vacant and deteriorating since Hugh Sharp’s death in 1968. It was recommended for demolition in 1998. The building still looks structurally sound, but the interior is in ruins. Plans were approved in 2009 to renovate Gibraltar and turn it into upscale office space, but no action has been taken.

This section of Wilmington has many elegant homes, and the SL550 looked right at home.

Why Is Everything Locked Up?

As I went looking for a few other sites in Wilmington, I began to realize that I was perhaps not in the safest part of town. You know you’re in a sketchy area when the public parks are padlocked… This one memorializes Fort Christina, which was the site of the first Swedish settlement in North America in 1638. The Swedes were constantly at odds with the Dutch, who had claimed all the land between Cape Cod and Delaware in 1624. After Peter Stuyvesant was appointed governor for the Dutch New Netherlands, he led a small army to capture Fort Christina, thereby ending the Swedish effort to colonize in the New World. Nine years later, the British drove the Dutch out of this area and took over the fort. It was rebuilt for use in the Revolutionary War, and again for the War of 1812, but today no sign of the fort remains.

The area began to look even sketchier when I discovered that the grounds of the Old Swedes Church were also locked up. Formally known as the Holy Trinity Church, it was built in 1699 by descendants of the original Swedish colony here. It is said to be the oldest church in the U.S. that is still used as it was originally constructed.

Across town (in the sketchiest area yet) sits “The Anchorage,” one of the stranger mansions I’ve seen. The section on the left was built in about 1820 for Jeremiah Woolston, who founded the National Bank of Wilmington and operated a 100-acre farm here. It has 12-foot ceilings and walls made of quarried Brandywine granite that are 2 feet thick. Navy Captain John Gallagher bought the property in 1835 for his retirement and gave it the name “Anchorage.” He had served with Captain Stephen Decatur during the War of 1812. In 1848 Dr. John A. Brown bought the farmhouse and surrounding land. The good doctor was apparently quite flamboyant and wanted to modernize the old place—by adding an incongruous pair of brick Italianate towers. The larger, 4-story one is seen on the right in this photo.

The smaller, 3-story tower is just visible in this picture. Dr. Brown also had the original stone house covered in stucco, much of which is now in the process of falling off. In addition to being a physician, educator, and political activist, Dr. Brown manufactured “1776 Root Beer” in Wilmington, which was apparently quite popular. He also used a portion of his acreage to create a new residential neighborhood that became known as Browntown. The City of Wilmington annexed almost all of the remaining land, reducing the Anchorage property to a single acre.

The fate of The Anchorage is up in the air. A developer has requested permission to demolish the house and build 40 row houses here. Local preservationists are lobbying against the plan, and the city council has tabled the request until more information is available. It may be a bit of an oddity, but the Anchorage deserves to be rescued.

Not Your Ordinary Pet Cemetery

After finding two abandoned mansions and some locked-up historical sites, I left Wilmington and headed for New Castle—originally a 1651 Dutch settlement named Fort Casimir. Just outside of town, I located the old “Glebe House,” which was a residence for the rector of the Immanuel Church. The original glebe house dated to 1719, with this replacement having been built in sometime in the 1820s. It remains in excellent condition and is still owned by the church.

The Dutch settlers were an industrious lot, and they set about building dykes in New Castle—not for flood protection, but to enable the marshes to be drained, thereby increasing the amount of arable land for farming. This photo shows the “Narrow Dyke” or “Foot Dyke,” built sometime before 1681. In 1675, “Broad Dyke” or “Horse Dyke” was also built to further add farmland and to carry a road across the marshes. Remember the New Castle Circle that defines the northern border of Delaware? Its 12-mile radius was originally measured in 1701 from the end of the Broad Dyke, which was the northern-most point in New Castle.

At this point, the Delaware River is approximately 1¾ miles wide.

Archaeologists have determined that Fort Casimir stood at this spot, based on artifacts found under 3 to 4 feet of old paving, “industrial trash,” and other more modern layers. A much more extensive excavation would be required to determine its specific outline, some of which would have to be carried out under existing houses, gardens, and parking lots.

All surveys of the New Castle Circle after 1750 (including Mason and Dixon’s) were carried out using the cupola of the old New Castle Courthouse as the center of the 12-mile radius. The current building was constructed in 1732 after a fire destroyed most of the original in 1687. The New Castle Court House Museum is now housed here.

One case tried at the New Castle Courthouse involved Thomas Garrett (1789-1871), the Quaker abolitionist mentioned in Part I of this report. Garrett openly supported the Underground Railroad, offering shelter, clothing, and financial assistance to enslaved African Americans who were seeking freedom in the north. In 1848, he was sued in Federal court by two slaveholders. His case was heard by the notorious Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, and Garrett was fined $1,500—which was enough to ruin him. Fortunately, his numerous Quaker friends provided aid. Following the verdict, Garrett stated, “Judge thou has left me not a dollar, but I wish to say to thee and to all in this courtroom that if anyone knows a fugitive who wants a shelter and a friend, send him to Thomas Garrett and he will befriend him.”

Views of New Castle are dominated by the Immanuel Church and its towering steeple. The church was founded in 1689, and the building erected in 1703-1708. A catastrophic fire in 1980 destroyed everything except the church’s walls, but repairs were made within 2 years.

The “Dutch House,” on the left in this photo, was built in about 1670 and may be the oldest house in Delaware. It is now owned by the New Castle Historical Society and houses a museum. It felt great to drive the Mercedes around with the top down. And I got a sincere compliment from a young fellow driving a slammed Honda Civic with a big wing on the trunk and hip hop pulsating from the interior: “Hey dude, that’s a totally sick car, man!”

This little octagonal building is perhaps my favorite in all of New Castle. It started life in 1892 as the town’s library. Construction had been delayed for several weeks as a result of rampant intoxication among the workers. The building was designed with no windows; light enters through skylights and continues into the basement through glass panels in the floor. And while it looks octagonal, only the front portion is shaped that way. The rear is actually rectangular. A new library replaced this one in 1964, and sculptor Maurine Ligon made the octagonal building her home and studio. Like the Dutch House, the old library is now a museum.

As for Ms. Ligon, after a very successful career she passed away in 1980 and was buried in a pet cemetery with her beloved collie, “Lady” (1957-1973)—the only human among 1,600 buried animals. (Photo courtesy of the Coalition for Animal Rescue and Education of Delaware.)

A Mansion Revisited

There are hundreds of beautiful old homes in New Castle. This one was built in 1801 and later became the Immanuel Church parish house. As shown in the old photo (courtesy of the New Castle Historical Society), the house is located on The Strand and looks out directly on the Delaware River. The Strand is subject to flooding during storms. If water levels continue to rise as expected, then New Castle will be in need of a new program of dykes—this time for flood control.

While you’re driving around New Castle, it’s not uncommon to spot something really unusual out of the corner of your eye.

In this instance, it’s the Lesley Manor, which is a beautiful Gothic Revival mansion that was built in 1855. It has 13,000 square feet of living space, 13½-foot ceilings, and many original features such as gaslights, speaking tubes, and an elaborate electrical alarm system. Dr. Allen Voorhees Lesley was a noted surgeon and medical pioneer who also served as Speaker of the Delaware State Senate. He wanted a home similar to the castle-like mansions being built in the Hudson River Valley—and he certainly got his wish! Twice in the past, the house has fallen in to disrepair, but each time it was restored by sympathetic owners.

While I was photographing the SL550 with the mansion in the background, I heard a voice behind me say “That’s beautiful!” It turned out to be Leigh Anne Moriarty, and she was referring to the car, not the mansion. I was soon chatting happily with Leigh Anne and her husband Frank, who are car and music aficionados and live next door to the mansion. Frank has written a number of books about NASCAR racing and rock legends such as Jimi Hendrix. He owns a 2003 Mustang SVT Cobra, one of the finest iterations of this classic pony car, and he also plays a mean guitar (which you can hear on his website loudfast.net. They are both big fans of Rush, and Leigh Anne’s favorite Rush song is “Red Barchetta,” which made the conversation all the more interesting. (For those who don’t know the story, check out The Drummer, the Private Eye, and Me.) As chance meetings go, this one was right up there!

Lesley Manor is surrounded by walls, tall trees, and other vegetation, which offer the owners substantial privacy but also make the mansion difficult to see. Here’s a photograph from the Historic Architectural Building Survey that better shows its elegance. And the more I looked at the place, the more I began to realize that I had seen it once before, back in 2011 (see To Have and Have Not).

Lindbergh’s First Choice

As I left New Castle, I spotted the old Bellanca Airfield hanger—all that’s left of Bellanca’s original design, manufacturing, and testing facility from the 1920s to 1950s. Bellancas were considered one of the finest airplanes made in the early 1920s. Guieseppe Bellanca was the first to place the propeller, wings, and tail in that order, which set the standard for all modern aircraft. In 1927 a Bellanca WB-2 circled New York City for 52 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds, breaking the existing record for flight time. Charles Lindburgh tried to acquire this Bellanca for his famous solo flight across the Atlantic but was not able to do so. A few weeks after Lindbergh’s flight to Paris, the same WB-2 flew the considerably longer distance from New York to Berlin.

The town of Christiana, DE is mostly defined these days by the massive Christiana Mall. If you look hard enough, however, you can find the original little village. Situated at a crossroads and at the head of navigation on the Christina River, Christiana quickly became one of the colony’s major hubs for transportation and commerce. It is named for Queen Christina of Sweden.

The Christiana Presbyterian Church was organized in 1732, with the present church building constructed in 1847.

Immediately next door is the stately Joel Lewis House, which was built sometime before 1799. Mr. Lewis was the town’s only hatter (and presumably a very successful one). The little fort-like structure at the front of the house is a later addition; perhaps a playhouse for children? If Joel Lewis knew of this odd modification to his house, he would have undoubtedly become a mad hatter…

The 1759 Shannon Hotel had a reputation for outstanding food. It served such notable visitors as George Washington (who routinely stopped in Christiana while traveling between Mt. Vernon and Philadelphia), the Marquis de Lafayette, and Benjamin Latrobe. In addition, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon are believed to have stayed here many times while they were surveying in the area. The old inn has been vacant for a long time, and Joe Harper, a former mathematics teacher, has been doing his best for the last 45 years to keep the place from falling down. The Christiana Historical Society has also stepped in to help, and it appears that significant progress is being made.

If you compare my recent photo of these two houses along Main Street with the older one, you’ll see that the houses haven’t changed much—except the little one has somehow managed to switch its door and first-floor window. I’m sure someone had a good reason.

You know you’re heading toward someplace special when there is a long, tree-lined driveway.

At the end is Buena Vista, which was built for John M. Clayton (1796-1856), who was a lawyer, judge, Senator from Delaware, and later Secretary of State to President Zachary Taylor. The original, 5-bay house was built in about 1845, with a number of additions thereafter. Remember T. Coleman du Pont, who owned the North Star mansion? He bought Buena Vista in 1914 and later gave it to his daughter Alice Hounsfield du Pont. Alice married C. Douglass Buck, who later became governor of Delaware, and, following his death at Buena Vista in 1965, she sold the mansion to the state of Delaware—for $1.00. It is now the Buena Vista Conference Center. As the National Register of Historic Places notes, “The newer portion, furnished basically as Governor Buck left it, is used for meetings of State agencies and for the entertainment of distinguished guests.” On this day, I chose not to test how distinguished I might be. (Photos are of John Clayton, Alice H. du Pont Buck, and the Buena Vista dining room.)

On my way to St. Georges, DE, I passed by the Fairview Mansion. Irishman Anthony Higgins built Fairview for his oldest son in 1822. Grandson John Higgins hired noted American architect Frank Furness to expand the home with a third floor and an addition equal in size to the original building but offset (the righthand-most section of the house in this photo). Note the unusual treatment of the roof, which had to cover both the old and new sections, and which overlaps the walls to keep the house from looking too tall.

Looking at the Sutton House in St. Georges, you would be forgiven for thinking that it is quite small.

Viewed from the side, however, the house is massive. The original portion was built in about 1794 by John Sutton. His oldest son James became a physician and operated a drug store in the first floor of the house. This historic home has been in the Sutton family through at least 2005, when James Nuttal Sutton, IV passed away. And it may still be, since James IV was survived by a number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

A Man, a Plan, a Canal: [Not] Panama

In about 1670, Czech cartographer Augustine Herman recognized that the Delaware River ran within a dozen miles of the northeastern end of the Chesapeake Bay. He proposed construction of a canal between the waterways, but no action was taken. The idea resurfaced in the 1700s—Benjamin Franklin was a proponent—since such a canal would greatly shorten the travel distance between the ports of Philadelphia and Baltimore. Construction of the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal finally began in 1804, ran into problems, resumed in 1824, and finished in 1829, having been dug by pickaxes and shovels. In the process, the canal came within 500 feet of the Sutton House in St. Georges.

This view of the C&D Canal shows the St. Georges Bridge on the du Pont Highway (which was proposed by our friend T. Colman du Pont) and the William V. Roth, Jr. Bridge on Highway 1 (named for the late Senator from Delaware).

With that, it was just a hop, skip, and jump back to Catonsville, Maryland, completing my trip. It had been a beautiful day, full of interesting history, dramatic stories, great scenery, and the opportunity to jump over an entire state. What more could you ask for? The Mercedes-Benz SL550 made it all possible and carried me quickly and comfortably from one site to the next, never missing a beat and never failing to enhance the journey.

Rick F.